Spring

well-tending

This week, while I settle into the refuge of the roads in USA, I’ll share something from my archive. This piece was originally commissioned for Dark Mountain 22 - ARK, and returns us once more to the shore. I have added photos and a map. I hope you enjoy it. See you next week with something new.

From Keepers of the Springs, 2022

Earlier that day I had begun to clean the well, or spring, or spring-fed ten-foot-long watercourse (no one agrees on what to call it). Overlooked by fishing huts in a cove tucked away, it doesn’t have a saint’s name or even a common name, as far as I can tell. I’d been coming to the cove frequently for a couple of years, learning to fish, learning to rest, sleeping with the sound of the sea and waking to the call of the kestrel as it hunted for lizards. That year, I often felt drawn to sit beside the well in the shade of the pollard ash, and wondered if it had always been filled with the strange rounded oblong quarry rubble pebbles that cover the beach and which children feel obliged to throw into the water.

Audio version

For no real reason I could explain, other than a strong physical urge, I began to remove a few of the hundreds of stones from the watercourse. Then, wearing rubber gloves, crocs, combat trousers and an old T-shirt, the day passed in meditative heavy lifting, subliminal grunting, and the occasional curse when I found broken glass or litter. The rubbish went in my bin, to be packed up the 150 stone steps to the bins at the clifftop later. The pebbles formed a huge mound to the side – I would deal with these the next day. After two hours, I was sitting on the top step looking down at what was now a small pool of slowly clearing fresh water, wondering how I could move all the silt and sand that had built up over the years, which now muddied the well.

After a mug of tea, I got the broom from my hut, and slowly, like some eccentric Zen cleaning lady, developed a way to sweep the detritus down to the outflow. I couldn’t just sweep; all the eddies would immediately return the mud to the source of the movement in fractal patterns straight out of the Mandelbrot set. Somehow, incredibly slowly, I had to push the silt down, then, suddenly draw the broom back to form a barrier to the backflow of the dirty water. If I hurried, the well silted up. If I did not sweep at all, the well remained silted up. I could not have asked for a better koan.

Two hours later, tired and quiet, I sat back down to look at the first sparkling white sand I had ever seen in the well, at the bottom of two newly excavated old stone steps. As I was staring into the water, feeling the ache in my back and looking at the holes in my gloves, a woman in old shorts, sporting a deep tan and thick black mascara approached the standpipe tap by the well and said, ‘The steps go deeper down, you know, there’s another two. Glad to see you’re doing that now. I used to do that, but I can’t now since my hysterectomy, see. It’s always such cold water, mum used to send me down here every day to collect it for the bucket to keep the milk jug cold. It always runs, it’s the only year-long running water on the whole island, this is. Really special, it is. Shame about the rubbish, the kids, they don’t know anymore. Think it just comes out of a tap. Don’t give it any thought. Anyway, as I said, so glad you’re doing that now. I’m Margery, what’s your name? Caroline? You have the huts just here, don’t you? Anyway, going to go catch the last of the sun now. Nice to meet you. See you later. You’re doing a great job there. Bye, love, bye.’

My face prickled and the hairs on the back of my neck stood up as I watched Margery flip-flop away between the toilet block and the front beach huts to catch the afternoon sun before it tucked behind the south cliffs of the cove. Everything I thought I knew about myth, responsibility and transmission was thrown upside down in an instant by this affable Dorset woman.

And with my ears ringing, and something between a sob and a giggle in my chest, it occurred to me that it is nothing like it says in the books. When the old keeper of the holy well passes on the sacred task of protecting the waters, there aren’t any capes or bells or dancing cherubs or goblets of wine, nor any ceremony beyond the unselfconscious, convivial oversharing that ordinary Dorset people recognise as good manners. As I sat, sweaty and scratched, in my baggy army-surplus trousers, I remembered all those Pre-Raphaelite paintings (which I secretly loved as a teen, and still love, despite myself) full of adolescent pale naiads, surrounded by their long, untangled hair. And I thought, Dante Gabriel Rosetti1 and JW Waterhouse would not be at all impressed with my scant bleach blonde ponytail and lack of flowing robes.

Only months before, while in the Cairngorm Mountains, I had been talking to the writer and performer Dougie Strang of his plan to visit ancient wells and springs in his native Scotland and to clean them. To return to the seasonal practice of our ancestors, which was to clear, maintain and protect our local water sources in the many thousands of places in the British Isles and Ireland where water rises to the surface as a spring and flows into streams or gathers in wells. These sources are the original holy places of these islands and their fresh, clean waters sustained humans and all other creatures.

Welsh myths and many stories from around the British Isles and Ireland speak of a time before keepers of the wells were disrespected. Traditionally women, the guardians of fresh water were always to be treated with reverence and never to be threatened. The stories also say that there came a time when warlords, bandits and eventually ordinary people no longer kept to this sacred agreement. This is when curses rained down on the land. It may be that these are allegories for a moment in history where land use and ‘ownership’ changed dramatically. When social mores and reverence for nature, as a place full of gods and spirits, changed to other ways of seeing the earth, and the transition to a faraway, authoritarian male god. What is certain is that we are still in the era of disrespecting water. My own local water board has been fined millions of pounds for pumping raw sewage into the sea and rivers. The Environment Agency in England, the public body statutorily tasked with protecting the land, air and waters, has just publicly stated it no longer has enough funding to follow up any but the most egregious or toxic examples of pollution. Wild swimmers come home ill with gastric bugs caught from untreated human effluent. Not a single river in my country is considered entirely safe to swim in.

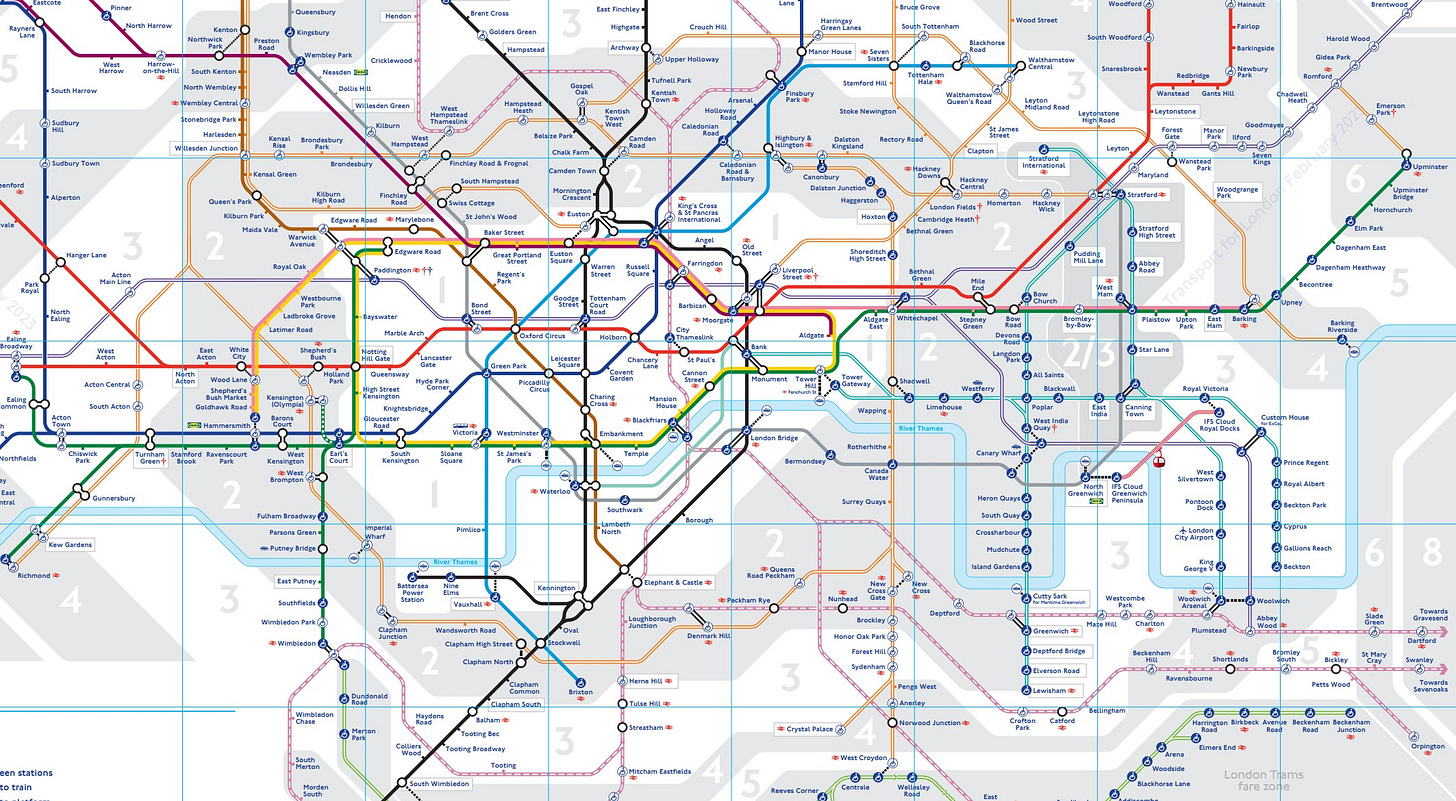

It is not only neglect; it is amnesia. The UK has countless places named for springs, wells, rivers and bodies of water, or with one of the ancient words for water in a landscape embedded in the name. To name a handful: Liverpool, Blackpool, Wells, Bath, Puddletown, Oxford, my hometown of Bournemouth (literally, ‘where the stream meets the sea’). Along with the many iterations of words for ‘hill’, water is perhaps the most common aspect of a name for a village, town or city in the country. And yet we move around our landscape as though the waters did not exist or were merely an encumbrance to the free flow of traffic. In 2009 Transport for London (TfL) caused uproar by removing the River Thames from public transport maps, deeming it unnecessary and causing the map to be ‘too cluttered’. Due to public demand, the light blue graphic representation of the Thames was swiftly reintroduced and still winds its famous looping shape across all official transport maps. The Thames is the geographical border between north and south London and is the great river into which all the smaller rivers of London drain. It is not a simulacrum. In seeking to obliterate the simple visual representation of the real, essential for orientation, TfL’s actions were only one of many instances of the abstracting and flattening influence of the machine mindset upon the land.

From the late 1960s to 1970, a new bypass called the Wessex Way was built where I live, passing through Bournemouth and cutting a score of roads in two, permanently dividing the areas of Charminster and Boscombe. My mother, now in her mid-70s, recalls with amusement the consternation of the road builders, when time after time the excavations for the Springbourne underpass kept unexpectedly filling up with water. ‘Springbourne’ means literally ‘where the source of the river rises’. The clue was in the name, or would have been, if they had remembered why things were named originally, based on the physical nature of the land itself. Expensive draining systems and pipes were laid, and after many delays the underpass and roundabout were completed.

Three years ago, the eel returned to the well in the cove. Margery said it used to come every year, and of course she knew it was not the same eel, but the strong physical urge in each new generation of eel was the same. The black eel writhed up the white stone beach and then slid down into the freshwater channel to the source of the spring. Sadly, the sweet water led nowhere for it to spawn. It met cold hard Portland stone right where the water bubbled up, as there are only ten feet of ‘stream’. After a day, a local man lifted the eel gently into a sandcastle bucket and released it back into the sea. Until I cleared the channel, it could not have come up, so it felt auspicious that it could visit briefly, following its primal urge, even if it was swiftly returned to the brine.

Later that week, I was doing one of my periodical clean-up days, quietly lugging rocks and sweeping algae and mud, getting covered in gunk. A local girl of around eight or nine years old watched me work.

After a few minutes she walked up and said, ‘Can I do that?’

I said, ‘Yes, anytime, if you’d like to.’

She replied, ‘One day when I’m a grown up, can I be the one who cleans the spring?’

And with a shiver of recognition I said, ‘Yes. Yes, of course. Just come and find me.’

This week’s good thing: Lean Logic, A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It, by David Fleming (Chelsea Green 2016) . Since I first saw this in friends’ homes, I wanted to have the time to read it. That never arrived, but a friend bought it me for my 50th, and now I read it entry by entry at each mealtime instead of the weekend papers. You will laugh, wince at your own assumptions, and know a whole lot more, even by page 18. It’s essential.

The rather wonderful Venus Verticordia by Rossetti lives at my local art museum and gallery, The Russell Cotes. Built up from a classic ‘Victorian gentleman’s oddities and art collection’, this place is well worth a visit if you are ever in Bournemouth.

As a member of the laptop class, I don’t get my hands into earth or water nearly as much as I want to. Yet earth and water are part of our identity, not in a political or rights sense, but more intrinsically. We often think that when we develop land with mass-scale brutish efficiency, we are doing something terrible to it, and of course we are, but we forget we are violating something in ourselves.

Thanks for such wonderful storytelling