Today I am writing to you from deep in the North Carolina woods, where I have been assisting Dr Theresa Emmerich Kamper teaching hide tanning. Time to write is scarce, as is wifi, so forgive any typos, and the informal tone, as I am fresh in from smoking buckskins. Hopefully I can get this out reasonably on time, and I’ll add an audio recording as soon as I can after 1st May. Our venues have varied greatly from camping in a clearing at Georgia Bushcraft to working in a beautiful property reminiscent of Sussex, England in North Carolina. Here we awake to the white tail deer, wild turkeys and buzzards, cardinals, skinks and wall lizards abound. Warm greetings from the green South.

Audio version

The embodied life

For me, even though I write almost every day, a hearty physical life is non-negotiable. There are thoughts I can’t have and feelings I can’t reach without access to the green. Similarly, I may be well in myself and reasonably fit, but if I spend whole days glued to the screen, I end up jittery and stiff, even if I don’t watch or read anything untoward. It is not only the timbre of what I see that affects me deeply, but the medium. Since the day before the World Trade Center attacks in 2001, I have not watched television or video news of any kind, only reading print, or online text based news with static photos. I would say that I am mildly averse to all video except well-made television programmes or feature films. Most of what I see online is text, and for the last year, most of the best of that has been here on Substack. I find the lack of adverts and flashing infographics much more conducive to reading and the page elements are pleasingly simple, unlike the aesthetic hell of Facebook, for instance. So, unlike many of my peers, I cannot blame screen burn on the content. The aversion to video has a good side effect for mental health. It is the act of sitting, consuming from a screen, that upsets my equilibrium.

Many of my learned friends, and plenty of people on this platform write regularly and deeply about the machine and its desires, what technology is doing to us and what the internet does to thought, discourse and culture. My own area of expertise is what all this is doing to our embodied organism as a whole. For years, students would come to classes at my school, Great River T’ai Chi, with injuries, pains, malaise or misalignments caused by a work-lifetime in chairs staring at screens. I always started by asking a new student what they did every day. People assumed I was asking for their job title and proceeded to tell me they were a CEO or administrator, a mathematician or a software engineer. But then I would ask, ‘What posture is your body in all day? Do you sit at a desk at a computer?’ If the answer was yes, then to me, all those jobs were the same. These days, in terms of embodiment, there are two main kinds of work – at the computer, or not. Then, of the jobs not at a computer, there are ones which nurture health and others that are neutral or damaging to it.

A few months ago in the comments I was in conversation with my friend

, author of Hagitude, about some of the ways we can maintain a healthy embodied life even if our work is mainly at the laptop. For a long time, many of my closest friends have been writers and I have often wondered what practical things could help those people whose livelihoods mean they can’t regularly disappear to the woods for a ruggedly rejuvenating week. Below are a few thoughts on what might help if you too find yourself tied to the keypad rather than spending your days being paid a living wage for graceful natural movement. And bear in mind that my heart’s goal is not to make a domesticated life more bearable, but to make a wilder life more possible. (My advice may make the former possible, but the river underneath my words flows towards freedom, not necessarily safety.)The Machine Stops

So much of our current predicament was laid out in Orwell's 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World, most readers focus on the ideological aspects, which are rightly lauded. Yet EM Forster’s much earlier 1909 short story The Machine Stops shocked me so deeply when I first heard it as an audio adaptation on BBC Radio 4, about 15 years ago. The story describes how all humans now live sub-surface on earth, each individual in their own tiny room, communicating via handheld screens, sharing only second hand ideas. The Machine provides for their every need… until it finally breaks down. Putting aside the uncanny prescience of Forster’s vision, and the claustrophobic atmosphere of the world he conjures, it occurred to me that during the first pandemic lockdown, life resembled the story to a chilling degree. I often write here about the negative effects of lack of touch, and of haptic richness in general, but today I will mention just a few things about full-body-movement itself. These are things that you may already know in your bones, but I find that seeing them written down can help us make the moves we need to, rather than think, ‘I should do something’, and then succumb to inertia again.

The Machine does not care if we are well or ill, only that we consume. It is a form of resistance to be well, rested, nourished and to be in connection with life.

Step away

Simply: we need a daily life beyond the laptop and our array of machines. So many things now achieved by computer processors were once made of many 'receive-only / not mediate' devices, which were at least partially convivial machines. For instance, in recording studios in 1990s, we had racks of effects with hundreds of movable connection wires, huge two-inch tape recorders, massive mixing desks which the whole band would lean over - all hands were needed on deck during mixdown. Now everything is achieved by one person sitting very still with a laptop much like the one I am using now. So many people sit all day at a screen and go home to 'relax' sitting still at a screen. Our bodies’ many cries for movement are inaudible under the background noise of distraction and dissipation.

Bad content is not necessarily the issue, it is the imprisonment of the body in an experiential jail the person does not even notice because the brain box is either being entertained, or thinking it's doing something very important. I am with Robert Anton Wilson here – be kind to the animal! I (literally) 'take the animal for walks'. My own lockdown health regime never really ended. I realised I’d caged my creature-being after lockdown curtailed my in-person T’ai Chi teaching. We need to walk our dogs and ourselves, cook, craft and ponder away from 'sitting still next to a machine' confinement. I always ask myself - have I made natural movements today, or did they all service machines? Side note, expensive contemporary gym equipment routines are to me pastiches of Victorian workhouse and factory movements. When I lived on a boat on the River Thames, I should have given people hobnail boots and endless sweet tea and they could have helped me carry the 20kg sacks of coal to my boat every week, and paid me their gym membership fees for the pleasure. Victorian Fitness – flat caps and flat abs. I missed a trick. But now that I am strengthening my muscles on doctor’s orders, I can no longer sneer, as I too am to be found each week, rowing on the fake rowing machine and striding on the Nordic cross trainer so that my crumbly hips can be well-supported by stronger, larger muscles. Such are the indignities of getting older with arthritis.

We need long breaks from electronic devices with screens. I think this should be self-explanatory. Interestingly, devices without screens, such as radios, mp3 players (remember those?) and even 'brick' style mobile phones do not force us into immobility. We can listen and walk, or talk and walk, if we wish. But when we stare at a screen we must either be still, or be oblivious, and the upshot of either is eventually disastrous. Also, we must look away from the world and those around us to look into the device, which is not convivial, not semi-permeable (to use Iain McGilchrist's great term from the second half of The Master and His Emissary) and measurably decreases right hemisphere stimulation. Whole days or weeks at a time not looking at screens is the medicine. I used to accomplish this by going on Zen retreat at Gaia House or solo silent meditation weeks in a hut in the woods at Sharpham Barn, but now I go to the cove I wrote about last week. No phone signal, no electricity – ideal. I have not brought up the usual 'attention economy' points today, as they are well raised elsewhere. My compassion is greatest for the impoverished mammalian reality of humans.

Mental hygeine

When I look at dogs racing along the beach and rolling on the sand I feel animal pangs. In my private physical life, I am doing much work to address this. Animal joy, land joy, are real and cannot be mediated. All I can say is: find yours.

Knowing why we are using a device is a form of essential mental hygiene. This is the one I find the hardest, as it is easy for me to go dance in my tiny kitchen while I make soup, or go for a walk, as I live in a peaceful enough place: many don't. I still have so many excuses to be here online, many of them to do with making a living. This is an insidious trap - the reasons we give ourselves to look at a glowing screen. I don't need to tell anyone reading this how easy it is to think of innumerable good reasons why we will continue to be online / on screen. Mark Boyle, of 'The Moneyless Man' and 'The Way Home' is the only westerner I know to have followed the ramifications of this to their logical conclusion, and then arranged his life accordingly, without contemporary technology.

When we are conjuring words from the mythic, from the real, when we are translating from nature to language, when we are writing with the sincere wish to aid the wellbeing of people, such as journalists uncovering corruption, or teachers passing on wisdom, we are doing work for a good reason. Yet we need to be scrupulous about making sure we allow 'the creature' time in natural movement, away from fixing the eyes on flat, glowing rectangles. Screen life is not freedom, it's consensual confinement. I am beginning to feel the immobility and acquired physical ill-being that it cultivates are as important as the vast array of ideologies that capture people on here. As when any of the 'sides' finally allow their bodies out onto the street, they seem more aggressive and coercive than ever before. The caged animal will seek an outlet for natural movement or go mad.

So many jobs in the last decade involve hard physical work instructed by machine algorithms: Amazon stock pickers, data farm mechanics, delivery drivers, factory farmers. Not only is the work hard and monotonous, but it is not even overseen by a human to whom one could appeal. Trades unions are doing much to insist on better working conditions, but exploitation is then often outsourced abroad, and is the unseen price paid for our immobility. The social justice warriors ordering their pleather sandals are not so unlike the old genteel ruling classes: in both cases the burdens of physical serfdom and material extraction are occulted and sent elsewhere for someone else to bear.

During lockdown, in the UK it became almost impossible to connect with services in person, everything moved online. Banks and post office branches closed, small shops and markets failed. It impoverished our biological life and forced our movements, community connections and social habits through a narrow funnel. Older people were cut adrift, their convivial preferences flattened and erased. Sometimes we seemed like little more than meat cogs to those in power.

Alternating movement and stillness

I developed one useful thing during this period, which I have cleaved to, and use even when writing intently: Good cop bad cop or flip flopping activities while typing or reading. If I must be at the screen or phone for more an hour, then I will regularly break for a period and do the washing, go buy milk, vacuum the flat, shell peas, make bread, or whatever task gets my body and hands moving differently and looking up and out at varying distances. This does not disturb my thinking or spoil my concentration. Something in my psyche knows that it is nourishment rather than disturbance to be asked to move and has learned to accommodate the process, like a stroke in return for a rub from a friendly cat. Sometimes just the act of standing and stretching gifts new thoughts, and I must quickly note them down before folding the sheets or emptying the trash.

Another change was to make my spiritual practice physical. Most old faiths and indigenous beliefs make sure to embody their worship through rites and do not rely only on the word. Many believe embodied life is a divine gift, so taking due care of this is surely a duty. For me, life as a human is an unparalleled opportunity – I cannot say whether such a blessing will ever again happen to ‘me’, so I choose to nurture the form I appear to have taken, neither to indulge nor to mortify the flesh. For me there really is no ‘flesh’ as distinct from mind, there is just the infinite complexity of being in all its collagenous, circadian peculiarity.

Don’t optimise productivity

Some things need to be done efficiently, such as packing for travel, or cleaning before guests arrive, but none of this needs to be done the way a machine would do it. Efficiency and speed are rarely optimal ways of doing things, when one takes quality of life into account. Slow food and slow travel have been popular with the rich in the west for a couple of decades. But even for those of us without the money for indulgence, a saner way of doing things can percolate through our home lives. This becomes harder the lower down the social pecking order we are, if we are marching to the beat of school, a boss, or debt repayments, it can seem impossible to move freely in mind or body. Somehow we must find ways to break free.

I have experienced first-hand how some religions heap shame on the human creature and do not encourage us to move well, outside certain monastic environments where communal physical work is part of devotion. In the charismatic church of my youth, the body was seen as a site of shame and the cause of suffering, running alongside the widespread, sad, and unprovable theory that mankind is somehow faulty in itself at root (rather than some people indulging wrong behaviour and taking unwise paths, as I believe). Taoism is the exception in the major world religions, and is closer to the many thousands of Indigenous, shamanic or earth-based practices still extant. For Taoists, the body is the site of practice and is not separate from the natural process of all creation. It is a microcosm of the universe. Unwise paths can be retraced, and better roads taken. Destructive behaviour can be stopped and healthier actions can be chosen. Descartes’ error and the Hubriscene age which it birthed have left us with a broken dream of false freedom from embodiment. 1 Dualists smash the boat we need to cross the river. This has led to a blatant denial of physical realities, disembodied totalitarian urges, and conversely, the utter indulgence of physical life, to the detriment of the spirit. From where I stand, or rather sit, on a deck in a strange land, watching two Canada geese amble between the trees, the ‘hard problem’ seems irrelevant. I am a guest here, in every sense.

I cleave to freedom of physical bodily movement, conscience, association and speech. It is our birth right to move and be moved by life. If you have read this far please get up and close the screen, turn towards the door, and if you can, go outside. I will meet you there.

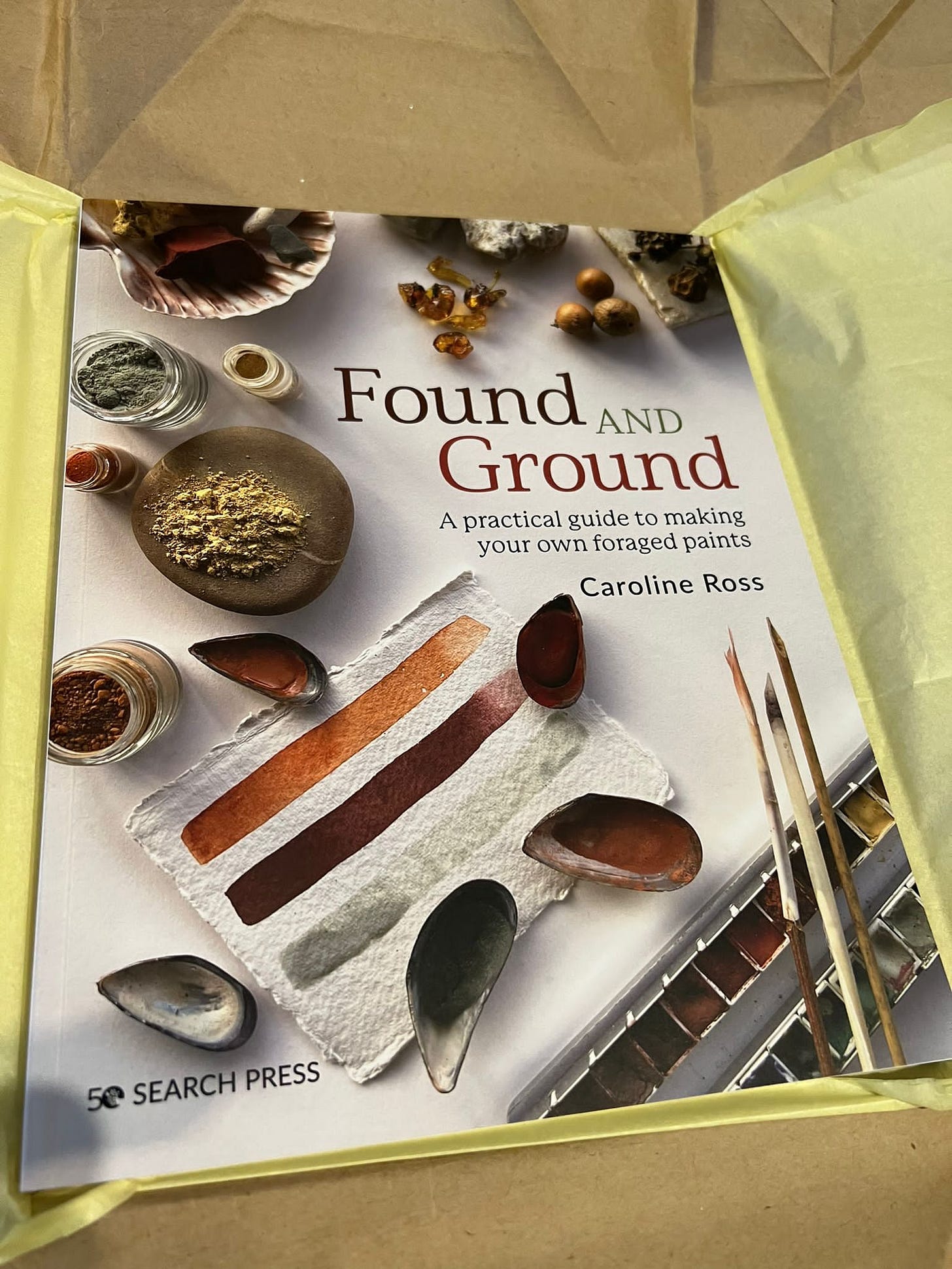

This weeks good thing: the author’s copy of my book arrived at my home in Bournemouth while I was in North Carolina, half a world away. My flatmate kindly unwrapped it and sent this picture! More about this and an invitation to the launch, soon. But for now, you can just search ‘Found and Ground book Caroline Ross' and order it in USA or UK at your favourite bookstore or online supplier. They are shipping in June UK and July USA. I have been so busy, I almost forgot I just wrote a book. At some point I will need to get my arse in gear, but for now, I am just very chuffed, as we say in England…

Freedom from the body is not freedom, it is to be a machine.

Wise words as ever, lovely. For me, interrupting the dream-state necessary for the kind of writing I do – especially when it's fiction – isn't much of an option; getting back to that place is incredibly hard work. But even if I do spend three hours in a trance typing at a screen, I don't think I'm really in the screen-world or Machine-world at that time; I'm firmly in some imaginal world where the muse resides. And, as the old 'Celtic' traditions tell us, that imaginal world is firmly entangled with the physical world. But what's interesting is that the inspiration itself is born from movement – specifically, from walking. Perhaps that entanglement between worlds is the reason. Like so many writers, my best ideas and images come not when I'm actually at the keyboard, but when I'm working my body, outside. The machine then is in service to the magic, not controlling it, but yes, we do still have to be very wary ...

Congratulations on the book!

Thank you for the great read. I suffered for well over a decade with back and neck pain from a run-in (or rather “bike in”) with a SUV when I was riding to work. My helmet, which I’d only just put on a few moments before, broke, which probably saved my head from breaking. Anyway, it was only when I quit my job, which was a lot of sitting in front of a screen, and started farm work (all hand tools, scything, hand sawing, digging) that all those “permanent” aches and pains disappeared!