The empty dais

It was twenty past ten and the spotlights were hot and bright. The raised dais and carefully draped couch were still empty, our pencils were all sharpened, there was a muttering in the life room. The tutor said, ‘Right then, who’s volunteering? One hour each, we’ll need five of you.’

It was 1989, early in the first term of my two years at Shelley Park1 art college, housed in the repurposed, characterful clifftop home of Percy Shelley, son of the writer Mary Shelley. The life drawing studio was on the top floor, accessed via a wide sweeping staircase, leading to the Photography, Graphics and Illustration studios, and then via a narrow flight to the garret, (originally for the servants, and reputed to be haunted by the ghost of a young chambermaid). This was the first time that term that a model had not turned up. Models were booked via an elaborate system of a self-appointed guardian of the list of Bournemouth artists’ models. Models were supposed to let the hirer know if they would be delayed or unable to come, but before mobile phones or email, this did not always happen. I was one of the five who volunteered to model (clothed) for my classmates so that we could get a good day’s drawing in after all. The tutor said I could have a stretch half way through. I chose a reasonably comfortable pose, or so I thought, and settled in…

If you have never sat still to be drawn before, then I recommend you try it as soon as you can. Perhaps you have an artist friend or a family member who likes to sketch. You will find out a great deal about yourself in a scant hour. You will also develop great respect for the many thousands of un-named people behind those famous paintings you know and love in almost every art gallery around the world. You will wince in sympathy with the models for The Raft of the Medusa, or The Incredulity of St Thomas. You will also know how it feels to be fixed in a very particular kind of gaze. Being scrutinised by someone who is sincerely attempting to draw you is transformative. It is as though the frequency of vision during life drawing is higher than in ordinary life. It is not cold, grasping and instrumentalist, like someone gazing upon pornography, nor entangled and positively-biased like a lover’s glances. Instead it is attentive, rigorous and prolonged. To be seen in this way is to learn to see yourself differently - not as object, exactly, and not as subject, provisionally, but as an essential pole of a fertile dyad. It is a uniquely rewarding kind of relationship, even if no words are spoken.

After my hour on the couch,2 I went down for a break in the college’s small canteen, and over a flapjack and instant coffee decided that figure modelling was exactly the paid work I was looking for. The freedom to sit and think, and to be paid for it! I obtained the number of the keeper of the list and called her as soon as I got home. As the only young female model I had work lined up within a couple of weeks. And that’s how, before I was 18 years old, I started to support myself by standing, sitting and lying naked, very still. It beat all my friends’ jobs: bar work in smoky pubs, waiting tables in restaurants or weekend shop work. I got to hang out with practising artists and listen in on countless variations of how drawing was taught. Modelling was, and still is, paid almost exactly twice the minimum wage for so-called ‘unskilled labour’. In 1990 I earned £12 per hour, and by the time lockdown brought an end to my modelling work in 2020, I was usually paid £20 per hour. Having left home with only £20 in my pocket, and with no savings or family wealth to augment a meagre grant, I felt very lucky to have found this strange niche.

A naked civil servant

My first session modelling at a local long-running Adult Education class was taught by a well-known painter who was a Royal Academician. After a few warm-ups lasting 5 minutes each, I was asked to hold a 20 minute standing pose. An experienced model knows just what pose can be held for just how long, but as a rookie, I had no idea. Taking a classic contrapposto position, heavily weighted to one side, by the time the pose ended my foot was almost dead and I was sweating from the effort of holding it in the overly-warm room. Never mind, I did not feel at all self conscious, which was a huge surprise to this usually completely covered-up hippy-goth. I felt free, capable, appreciated, and useful, all novel feelings. The £24 cash in my hand and a lift home were also very welcome.

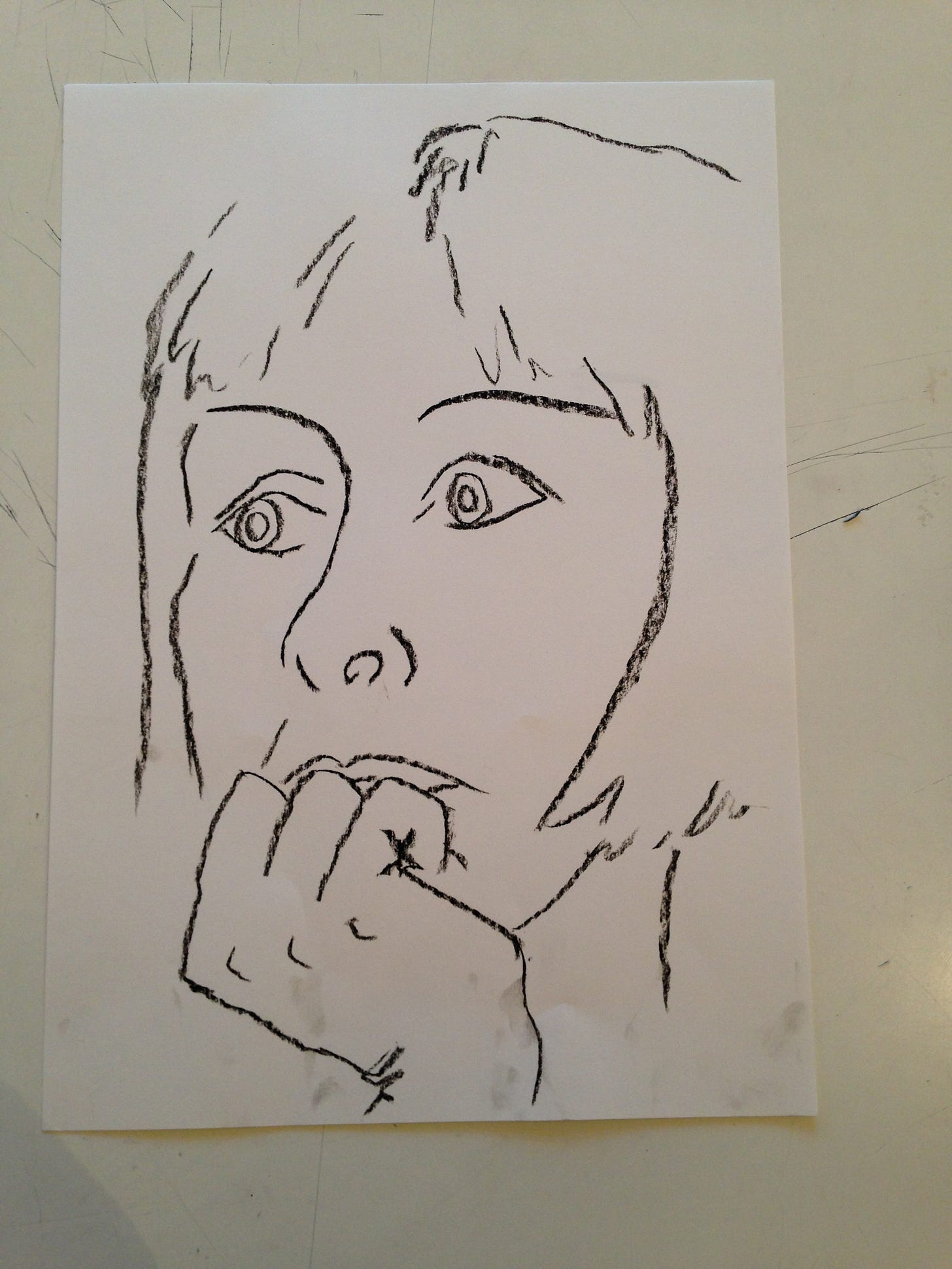

I was lucky to have had such a positive experience of my first times modelling and not be working in the era of assumptions that a figure model equalled a prostitute. Nor have there ever been even the slightest hints of impropriety from artists I worked for, as writer and model Anaïs Nin describes of Paris in the early 20th century, or countless British models experienced with the late Lucien Freud. No absinthe or digestifs for me in nineties Blighty, only McVitie’s digestives. Much of this good fortune was due to knowing the other side of the easel, having been a regular student of figure drawing for 3 years, I already felt at home. The art department at Bournemouth School for Girls had open life drawing classes, and we had a wonderful, dour, middle aged model who came and sat like a rock for us. There are very few pictures of my drawings from before I got a digital camera in about 2006, as all my slides and portfolios were lost in a fire, but here’s a classic school student ‘headless’ charcoal study I made of her when I was about 15. The one time she didn’t turn up, my teacher sat and read a book, which looked like a great way to spend two hours, so perhaps the die was cast early…

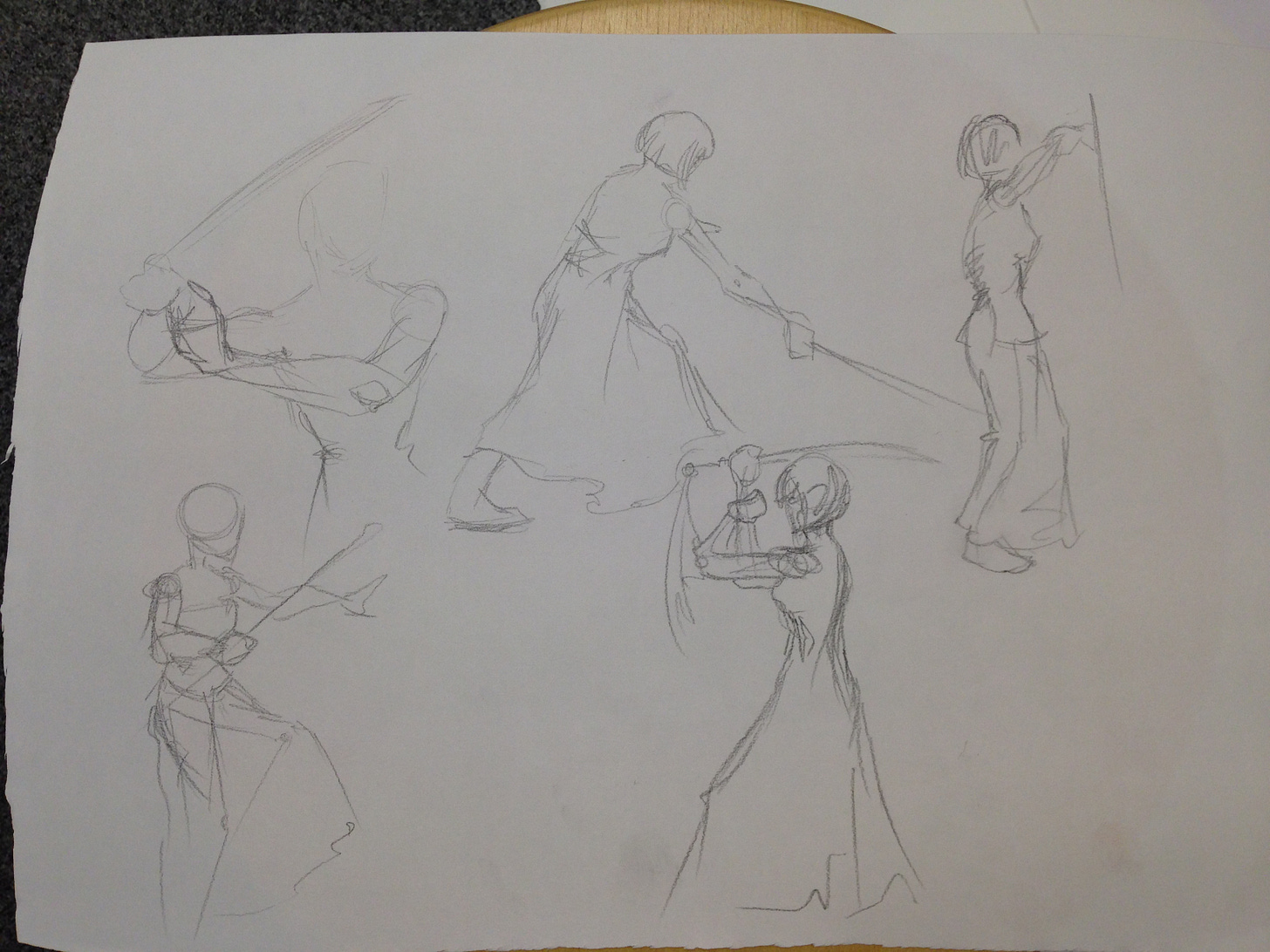

Eventually I had enough regular modelling work to pay my rent and save up to go to India with my boyfriend during the summer break. I regularly modelled for a drawing group run by an artist who told wonderful stories about drawing gay icon and raconteur Quentin Crisp, (who wrote The Naked Civil Servant3, immortalised by John Hurt in the film of the same name). He was also the subject of Sting’s hit Englishman in New York.4 The artist described how Crisp would hold the most strenuous of inverted poses - elbows on the floor and legs cantilevered upwards behind him in a chair, while keeping his wry smile and famous lilac coif intact. I found this new information intimidating. Were my poses too staid? What was my special skill in modelling going to be, (as it certainly wasn’t long standing poses, due to low blood pressure)? I decided to become really good at imaginative and unlikely short poses, sometimes based on postures from the T’ai Chi forms. My growing knot of rope-like ginger dreadlocks and my naturally very pale skin meant I didn’t look like any of the other rather tanned and solidly-built models, and this was a bonus. During lifts home in the artist’s remodelled ambulance, I asked him about what made for a good pose. He said to think about what I would most like to draw, and then take that pose. It was excellent advice.

Uniform

Standing naked in front of strangers may seem like the plot of your worst anxiety dream but when you have prepared and chosen the task, it is in fact an oasis of calm, personal time. Your mind is your own. Unless the heating malfunctioned, or on the very rare occasions where I felt ill, modelling has provided me with the time and space to think creatively, plan, or mull over ideas. For 30 years on and off, apart from when I was in a band, and until the first covid lockdowns curtailed all my in-person work, this job topped up my bank balance when art and T’ai Chi alone could not. I have never hidden the fact I did this work from anyone. In a town where every teenager was trying to look cool on the beach, I loved this alternative milieu of people not even minding if I had shaved my legs or wore any make up, so long as I turned up and posed well. It reset my beauty standards, and by turns opposed, reinforced or contrasted interestingly with the messages I received in The Beauty Myth, Our Bodies Ourselves and Spare Rib, (my reading matter of choice in those days, as antidotes to the ever-present laddism).

My simple work uniform was this: shaved armpits and legs, silver toe nail varnish, small silver earrings, mascara. Sometimes one or two of these were not present, once or twice, when filling in for an absent model locally, I would be out getting groceries when I got the call to dash to a school in Wimbledon or Clapham, and then I’d just turn up as-is. (Only fully background-checked models can work in schools in the UK, so my always up to date Police clearance meant that I was busy.) The small rituals of getting ready would make me feel professional and prepared. Plus, it was a courtesy to the many high school girls for whom I modelled during my last 10 years. I remembered from school how it might be a little daunting to see what happens to our bodies for real, not on a screen or at a distance, but close enough to see the stretch marks. And so, with their experience and ease of learning in my own mind, I attempted a kind of middle-way-approaching-middle-age ambassadorship: not too scary hairy, not too primped and preened. There are many strands of feminist thought, cultural suppositions and frankly pointless battles that could be waged over the warzone that the culture tells us is a woman’s own naked body. From the other side of the gaze, an entirely other view emerges, one based on embodiment. Modelling and T’ai Chi constantly informed each other; ease, stamina and rigour were needed for both. So, for me my body was never a battleground, but a proving ground.

The virtuous triangle

You’ve probably seen something like the ‘iron triangle’ above before, where you can only have one or two of the sides, but not all three. For instance, it illustrates that a high quality job done quickly will not be cheap… As someone who has studied and drawn at life classes, taught life drawing, and also modelled in similar classes, all for many years, the inherent goodness of the life drawing studio was very clear to me. As I have mentioned in the last two posts, diagrams get me thinking in a different way to prose or drawings, so I came up with the virtuous triangle to sum up these experiences. In this one, you can have all three sides, and all of them are good. It symbolises for me some of the sanctity of good learning environments. It also reminds me that when I am modelling, teaching or drawing, I could have in mind my connection with, and responsibility to, the other people in this relationship. As a teacher this means one takes care with the timings and breaks for the model and attends to the unique learning needs of each student, rather than imposing our will on the lesson. I have modelled for many hundreds, if not thousands, of life drawing lessons, and drawn or taught at hundreds. The best teacher I ever modelled for was Emily Burton5, who teaches in the Kingston area of Greater London. I learned so much while working with her, and we became good friends.

Anti-meditation

Perhaps you might be thinking that I had a wonderful opportunity for a few decades of paid mindfulness practice. Meditation can be done in almost any circumstance, and indeed, in my tradition, that would be the ultimate goal. In an early BTCCA handbook, my Grandmaster wrote of T’ai Chi that it trains us in, ‘At first, yoga [union] under special circumstances. Later, yoga under any circumstances.’ Traditional martial arts teach us to meditate - attend to life wholeheartedly - even in the middle of a fight. The Taoist Classics also repeatedly state that meditation practised in the midst of ordinary life is preferable to seeking refined states of mind only in peaceful seclusion. With this in mind, I attempted quite a few times to practice simple ‘sitting’ whilst sitting in extended poses for classes.

Until I saw some drawings produced by artists good enough to truly capture my likeness.

That fierce face! The slack jaw and the thousand yard stare that came from a relaxed temporary disinterest in the self. The results of my Zazen experiments were in: it was unfair on those paying to draw me. What good modelling requires, especially if someone is drawing for portraiture, is an engaged yet somewhat neutral expression. At first I attempted this by just doing lots of thinking in words, planning and ruminating. I soon found this was the equivalent of practising anti-meditation, and although it kept my mind alert and prevented sleepiness, it had a deleterious effect on my mind, even after the class ended. I didn’t want to be undoing my mind-training every time I took off my clothes.

It took years longer than I like to admit for me to find the ‘just-so’ practice, an inner smile. I didn’t suddenly become like the Mona Lisa, with an inscrutably amused expression, but I did pull back from the completely, (and if I am honest, almost corpse-like), toneless facial musculature of true meditation. The transformational moment was truly realising my place in that triangle above, that far from being a passive lump surrounded by people drawing or teaching as the creative forces in the room, I too was an active participant. I listened with more care to the lessons and to the sound of people drawing, to the conversations and corrections. I found that I could almost see the drawings being made, even from the far side of the drawing board if I didn’t dwell on my own thoughts so much. When I checked on drawings during tea breaks, I would find that I had correctly mentally ‘drawn’ what was visible. This way, I feel I finally benefitted greatly from the good teaching in the rooms, while staying engaged, alert and responsive as a model.

Staying with discomfort

There were hard sessions: extremes of heat and cold, challenging, uncomfortable poses followed by, ‘Could you just hold that for another 20 minutes?’ after I had timed to the moment how long I could bear the twist. There were the periods of tumultuous or upsetting life events that would monopolise my mind for each entire session, leaving me exhausted and drained even amongst the lovely company and good music. I had only four really unpleasant personal experiences in all my years modelling. At the most expensive private school in London the teachers and students all invaded my personal space with complete disdain and treated me like a servant. A little research online told me I was more well qualified to teach the poorly-run lesson than the teachers there. Similar experiences in a rough east London school and a new, cramped, Christian Academy showed me that it was not really the kids’ fault, but the bad examples set by their teachers. There is a proper etiquette for such clear power-discrepancy in social situations, as in hospitals, or even at the beach, where one person is unclothed and thereby rendered vulnerable. It is to give all due care and attention to the disrobed person, giving them a designated place to undress and to make sure no-one brushes past them. Another time, I was convinced an artist hated drawing me as he harrumphed his way through a huge preliminary charcoal sketch. I turned out to be wrong, he always moaned and complained to himself as he drew, so, could I come back regularly for the next 6 months?

Naked Stoicism

After the lockdowns ended, and many sudden life changes, I was back in the town where I first learned to draw. I had promised myself to stop modelling by the time I was fifty, as draughty halls and long poses can aggravate arthritis pain. I have no regrets, it has been an illuminating ancillary career. The insights, friendships and income were all welcome. To sit naked for someone in this context, in my country at least, is to be reminded I am a free woman and am part of a long-standing artistic tradition, going all the way back to Ancient Greece. Perhaps I am part of a secret hermetic branch of Stoicism, gymnós stoikós, where our mental and physical composure and endurance is embodied, rather than expressed in words. I like to think so. Over the years my mind would often wander to the latest news from somewhere where a woman my age had been stoned for adultery, (usually meaning she was raped), killed for an ‘honour’ crime, or banned from public life and education completely, as is now the case in Afghanistan. The privilege to be a woman, present in an educational environment, naked, safe, appreciated and well paid was not lost on me.

Showing up is my job, whether as model, artist, or teacher, whatever it is I am teaching. This work cannot adequately be done virtually.6 Embodiment is not New Age, and not just for athletes or lovers. Modelling contrasted superbly with my internal arts practice, I could not be serenely holier than thou, but instead I was sometimes keenly aware that I was sweaty, awkward or uncomfortable, a body in a space amongst other bodies, a mammal, a human.

By the end, after a journey through three decades of many kinds of presence and occasional emotional or hormonal weather that flushed my skin so red that artists asked if I was ok, I finally settled on just being with it all. Peri-menopause’s rages turned up the heat in my thoughts in an interestingly uncomfortable way. Until, after witnessing every mood my mind could throw at me while remaining obliged to sit and just bear it, something transformed. The almost anti-meditation turned full circle into an un-judgemental space in which my thoughts could arise and fall. It was as though my own mind and body became a spacious life drawing room, and my work was to pay attention to the inner model, the creative process, drawing well, (aka getting the mind just right), so I could see things as they really were. If I made a mistake, I could have another go. I can’t show you on paper any of this work I did. Like T’ai Chi, it leaves no visible trace. Or, maybe something here, now, in these words.7

This week’s good thing: I know I am late to the party, but I am enjoying

very much. Hence, I am unsuccessfully attempting not to do too much ‘psychopath spotting’ in groups of people on crowded trains to and from West Dorset.Shelley Park was the Foundation studies annexe of Bournemouth and Poole College of Art and Design, BPCAD, (now subsumed into Arts University Bournemouth - AUB). Though barely researchable, (partly due to AUB not valuing the contribution its predecessor made to its evolution), its alumni include a huge variety of socially aware and technically skilful artists in a wide variety of specialisations, for instance, Dryden Goodwin.

As illuminating as many at a therapist’s office, or on a zafu.

And also one of the influences on why this Substack is called Uncivil Savant.

I still can’t be sure that Sting really knows the hidden meaning of his own second line, ‘‘I take tea, my dear.’ Was he aware of British Gay slang in the nineties? I like to think he was in on the joke.

She does not have a website. I will show you her superb drawings as soon as I can.

People draw from life drawing classes on screens too, now. But this is translating a two dimensional image into another two dimensional image, as with photos, and is neurologically a far simpler task, with no need for mastering parallax, rendering internal perspective or scale. One can certainly practice technical skills and style, but it is as different as recorded music is to a live gig.

I’ll return to some other insights gleaned from modelling about the body, the erotic (and its opposite), negative space and embedded contexts in later posts.

Lovely, Caro--reminds me, somehow, of this William Stafford poem:

An Archival Print

God snaps your picture—don’t look away—

this room right now, your face tilted

exactly as it is before you can think

or control it. Go ahead, let it betray

all the secret emergencies and still hold

that partial disguise you call your character.

Even you lip, they say, the way it curves

or doesn’t, or can’t decide, will deliver

bales of evidence. The camera, wide open,

stands ready; the exposure is thirty-five years

or so—after that you have become

whatever the veneer is, all the way through.

Now you want to explain. Your mother

was a certain—how to express it?—influence.

Yes. And your father, whatever he was,

you couldn’t change that. No. And your town

of course had its limits. Go on, keep talking—

Hold it. Don’t move. That’s you forever.

A fascinating and beautiful account. Thank you.