This longer piece is a response to a recent essay by

and an opportunity to expand on a letter to my friend . I’ll raise the case for haptic richness over the tyranny of frictionless surfaces, show how our ancestors left us plenty of medicine in unlikely places, and suggest that there is no time, or at least no linear time, in the palm of your hand. For help from Blake, my mother’s sewing kit and a German biker, plus several contrasting photos featuring my hands, read on or press play.Audio version

Touch is unalloyed presence.

Not this writing, not my words in your head, not your thoughts about these words. But the pressure of your bum cheeks on your seat. The sensation of your clothing’s fabric against your waist, your top lip against your bottom lip as you push them together slightly more as you read this line.

You remember, those two years at sea with barely a port call for embraces, half the world and I went mad for lack of touch, or fear of it. Abandoned into the machine time of an evenly spaced, socially distanced queue, globally billions experienced what it is often like just to be British: seemingly constantly waiting for something ordinary, for an unspecified amount of time, outwardly blank and quiet, inwardly seething.

Since school I have wondered about the intriguing French word for ‘now’, ‘maintenant’. From the word maintenir (maintain), derived from main (hand) and tenant (holding). The word supposedly referred to the period ‘while something is being held in the hand’.

When we cannot touch, cannot be held, do not regularly make things with our hands, work so hard that we do not have time to press seeds into the ground in a garden, nor to sew the button back on our shirt, which is so cheaply made we throw it away rather than invest our precious finger-tip-time, which anyway we must keep sacred for our devices… We no longer settle into the never ending now-time of the hands.1 And thus, with a cold excision, we are severed from the real. A cut which is so hard to discern and so sharp we barely feel it, as after all, how many of us train to notice absences? Perhaps only wildlife trackers, thieves and martial artists. Where there is no touch there is no now.

I am not saying, ‘Oh wouldn’t it be nice if we all made handicrafts again’. I am saying: a primal cultural inheritance of goodness has been stolen and colonised by the Machine and barely anyone has noticed, and even those that do, such as this eminent surgeon, do not realise the all-pervasive ill effects of the disembodied life hyper-modernity wills for us. It is as though we are falling down a very high cliff, and on currently feeling no pressure or pain, wave and say ‘It’s fine so far! Not sure what the big deal is about not touching anything or anyone!’

Reclaim tool use from machines

I was thinking about the section in The Master and His Emissary where Iain McGilchrist writes about how musicians experience their instruments as alive. Brain scans of musicians playing find that how they relate to holding and playing the cello or flute, etc, is almost the same pattern of right hemisphere stimulation as for holding a living child or animal. The practice of music, in this case, goes beyond technê, and once proficient and at home in music, the musician relates with what elsewhere in society has mainly become an 'exiled capacity', which is to experience the vitality of all things, and the interpenetrating living modality of the seemingly inert. To their brain, and in their mind, the instrument is alive.

This is usually perceived by anthropologists as only an Indigenous skill, belief or tradition, but my understanding of it (and a winding path of my ongoing research in life) is that this skill is universally available and has only been temporarily obscured. If found at all in the Global North and other hyper-modern societies, it is usually hidden in crafts and traditional skills. In T'ai Chi, there is much written about the living spirit of the sword, when used by a master, how the metal comes alive and is imbued with ch’i (qi). Many see this as metaphorical, but I have seen it with my own eyes. It is not only the projection of intent and the mastery of skill, it is the melding of matter and heart-mind (hsin, xin, nous), perhaps quite like what was noted in the brain scans of musicians. Basket makers' willow, calligraphers' pens, Thomas Keyes' spray can, all may become Schrödinger's tools.

Underneath technê is hidden vitality, a river under the road. Tool use apparently gave humans the edge, we know the story, I won't repeat it here. Tool use helped bring us to this awful place, but in our desire to erase paradox and complexity, we can wrongly condemn humans as does Agent Smith in The Matrix. We ignore and discount any mention of what beneficial transformations the tools have done to us. (Incidentally, tools and machines are not the same, although there is a continuum between them.) Sadly, people seem ok speaking about themselves as machines, as being 'hardwired' for this or that, it seems normal to assign oneself the simplicity of machinery rather than face the organic mess of lived reality.

It is similarly easier for people to imagine the end of the world than an alternative to modernity, capitalism, or the Machine, (a nihilistic lazy urge Vanessa Machado De Oliveira writes so well about in Hospicing Modernity). And yet, the musician and craftsperson, the swordsman and the gardener are tool-users beyond compare. What happens to them / us is that without conscious thought, or effort, we are transformed and so are our tools, both gaining in vitality and capable of being-in-relationship, indeed, connexion. Also, that which is well taught in person, by hand, in a tradition, is so full of this quality that we may still speak of it as 'transmission' or 'lineage', not necessarily because of hierarchy, but due to the clarity with which embodied skills can be plainly seen to have been passed on.

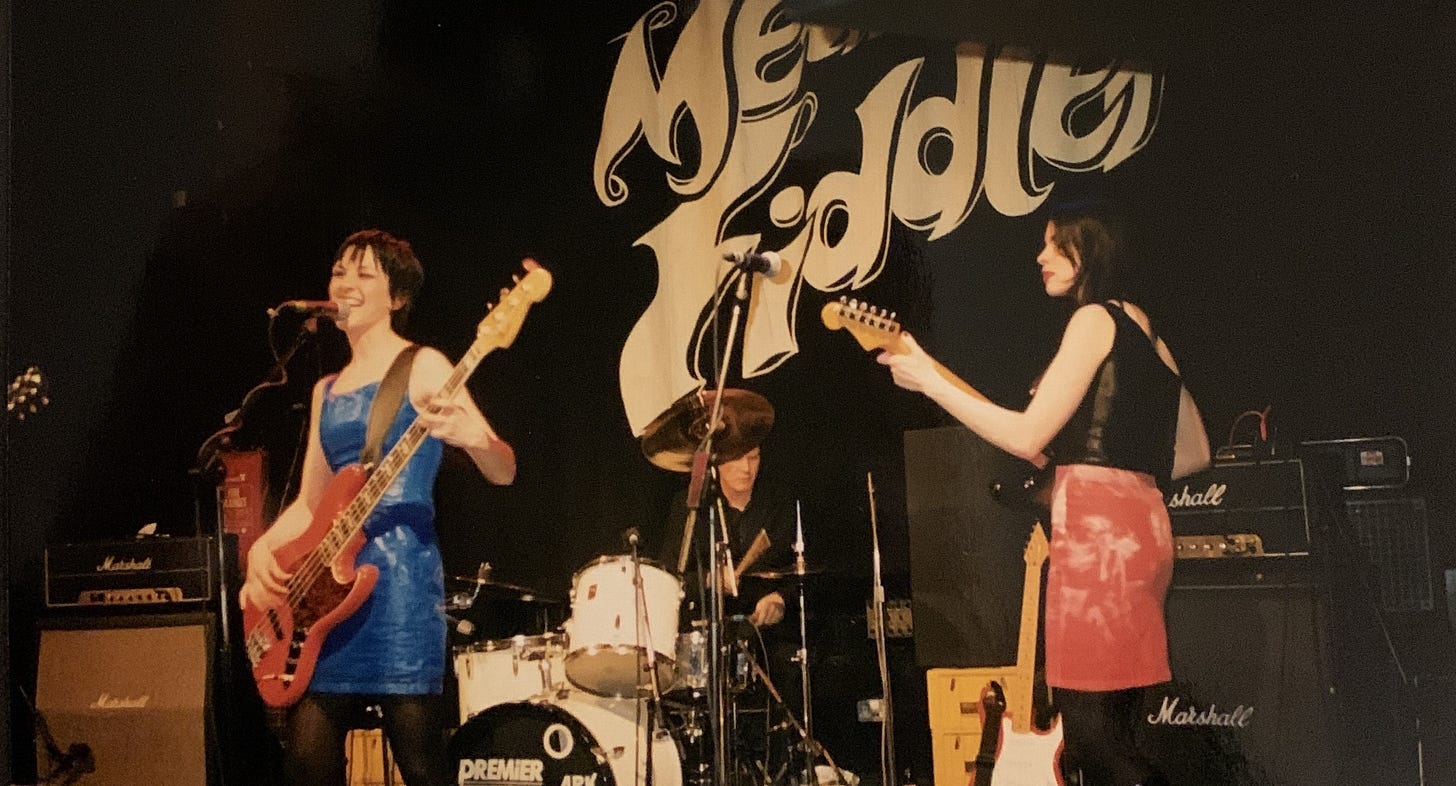

I went through a phase of thinking 'tool use was the Fall', but I have changed my mind. Putting what I have practiced and read together with what Iain McGilchrist researched, what we often talk of at The Long Table, and what Vanessa makes clear in her book, has shifted my overly simplistic view. When education only consists of what can be coded into written words and numbers, then we are at the apogee of left hemisphere processing and are indeed behaving somewhat like machines. But if a tool, let's say a bass guitar, is used by the hands and heart until the point of becoming alive to us, has not real magic happened? Is not the inert reenchanted, and revivified? What happens to the musician which we overlook here in modernity, is a thing Dougald mentions regularly - that his Indigenous friends find so hard to tell him that we're missing - because there are no words for it. It is how the water is for the fishes. The entire earth is alive, and everything in it. Not a belief, but an experience.

Gather medicine

Disney’s Fantasia scene 'The Sorcerer's Apprentice', the spindle in so many fairy tales, the othering of magic so it can only be seen as evil, rather than part of everyday life. So many images of the over-culture's attempts to prevent us from coming full circle into the aliveness on the other side of tool-use. The dire warnings of spinning, sewing, weaving, cooking, cobbling, woodcutting, hunting, are manifold. Where are the stories of the wisdom and joy that comes beyond tool use going into wu wei, no-tool, no-user? They are there in Zen and Tao, where even sweeping with a broom is revered, but I can't think of the like in my own culture. We won't get back our sanity by importing spirituality wholesale from elsewhere and not everyone has decades spare to devote to martial arts or music. We have to gather our own medicine, and I think it's in the long weeds: with the minstrels, bodgers and illuminators. Logos will not like it at all.

I make my late nan’s Scotch broth and linear time does not exist as I stir stock made from chicken bones and finely diced onions. The taste of eternity and Aberdeenshire blend when I dunk the bread and butter in it. While I sew back on the dangerously dangling button, my mum is here in my hands sewing it on with me, and her mother and her mother and her mother. My teacher’s ward-off (peng) is sometimes in my body too. Occasionally he says he sees his teacher’s hands in mine when Brush Knee and Push is just-so and I am not bound up in self, but am instead attending to the unloading step and the gentleness of my foot meeting beloved earth.

Transmission

Pushing a stranger’s hips during a class at Tai Chi Caledonia one year, I had the familiar, strange and wonderful feeling of falling into emptiness, as he yielded to my push and directed my force down into the earth. I straightened up and grinning, said, ‘You have studied with Dr Chi Chiang Tao!’ Shocked, my new German friend Walter, with biker’s leather jeans and a shock of white hair said, ‘Yes, for one week in Dortmund in 1986…’ and went on to tell me how my great Grandmaster was impossible to push, like a cat, utterly present but completely ungraspable. He said, ‘The only thing I learned about him that week was 1: that he had glasses and 2: that he wore a jacket, and that’s all I would ever feel of him.’ I never met Dr Chi, but I have felt his top student, John Kells, and my teacher, and a few others of his line in whom yielding was so deep that the sensation of falling began as soon as you rested your hands on them. When I met this stranger and felt these things in 2008, I knew at last in my body what transmission was. Time collapsed, and the present moment linked me to unmistakable haptic wisdom, but also to the seeds of understanding a way of being so rare in our culture that people don’t believe it exists. But it does. It is more often held now by traditional basket makers, hedgers, choristers, or the workers of endangered crafts. I am not saying these people are themselves the answer, but instead, that once common ways of passing down embodied tactile skills still contain some of the how that we desperately need. (The what will take me a few more months to outline here.)

A central tenet of the western mystery tradition is that within poison hides medicine. Perhaps we must pick up the rocks once again, very differently. Rather than hurling them at the obelisk and each other, we might notice the cool, moist imprint of the stone on the earth, where the woodlice gather, and also discern the ochre in the rock. Patience, ability to continue through frustration, feeling that one is part of a tradition, and the sheer trickiness of learning hand skills are lost to modern education, so these sources of medicine are missing.

Colonisers banned traditional crafts and ancestral practices wherever they went, or otherwise stole, appropriated or obliterated them. That the west has now successfully done this to itself and thereby suffers a profound spiritual displacement, seeking healing where it once trampled, is deeply ironic. Steiner education occasionally over-states cultural handiwork whereas state education completely ignores it, and I am not saying it's the complete answer, but it is a place to look. It would be rather fine to begin to dismantle the Machine with the simplest convivial tools made of resonant wood, catgut and a horsehair bow. These are a few things I am mulling over, literally, as it happens, on my glass mulling slab. Embodied metaphor is the form of the pill I choose. Familiarity with a physical practice or two is essential, as it gives me a rich supply of lived, repeatable experience, which becomes a vocabulary which is then carried across to ideas via metaphor. These blessed periods, suspended in the bright fermata of ancestral time as I make paint, are medicinal.

Hold infinity in your palm

Rhyd Wildermuth wrote last week: ‘The jetztzeit can only be recognized by rejecting linear time and the story it tells about the world. There is neither progression nor regression, no primitive Edenic state nor advanced future civilization. We are neither fallen sinners nor enlightened elect, and most importantly of all we are neither the products nor the protagonists of history.’

In relation to Jetztzeit / now-time, a term from Walter Benjamin2 I did not know until this week, I would like to follow on from what David Stevenson3 said in the comments below Rhyd’s piece as it brings together the hand, the word and time.

David wrote, 'So, when we tell ourselves "I am this, or that", or "I am like this, or like that" we are reinforcing a limited idea of who and what we are. The challenge/opportunity to step outside of time would therefore require that we step outside the confines of our identification with our collective history, and our identification with our personalities.'

I feel this intuition is correct, and habitual identification with thought forms and labels has a profoundly parasitic effect upon both one's natural energy and the ability to join with others, the earth, and life itself. The moment we tell ourselves, using the voice in the head, what it is that we are, we effectively cut off a vast field of possibility and create a reassuringly simple, machine-like, flow-chart of responses and acceptable personality traits. For instance, it is perfectly possible to make art every day of your life and not need to use the word ‘artist’. Indeed, that would have been the norm globally, until the Early Modern era. Briefly, the way out of this temporal and energetic confinement is something John Kells called 'yielding to our conditioning'. This is the work of years and certainly includes a psychological component, but it is at heart a spiritual task, counter-intuitively best approached with the body. I’ll be writing about the method in future posts, as well as the parasitic nature of certain kinds of thought, in particular - opinion.

The uncontrived immersion of Blake's 'infinity in the palm of your hand' is neither unreachable for the regular person, nor far off, in an afterlife. It is the fundamental ground of being. The hard work is not in grasping it, it is tediously, repeatedly putting down over and over all the shiny definitions we constantly pick up. That's why apophatic meditation, koans, pilgrimage, and in my case, getting pushed over for about 20 years by my teacher, are such good methods. My rule of thumb: If your current thoughts about yourself can survive it, the practice is not fit for purpose.

I realise that it is possibly heresy to say this, when everything seems to be about identity. But there we are, I am more interested in vitality, energy and spirit, and a very large part of me had to die, in order for there to be enough spaciousness for them. By putting down words in the mind and by picking up simple, beneficial tools with the hand (the wooden spoon, the paintbrush, the needle, the basket, the breadknife) we train ourselves not to grasp at things, at people, and at life. Instead, we open a door into an adult relationship with the ten thousand things where those things do not use us but instead become aids to sustained, immersed embodiment. Ancestral time, eternity, now-time.

Auguries of Innocence (two excerpts)

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

…

A Truth thats told with bad intent

Beats all the Lies you can invent

It is right it should be so

Man was made for Joy & Woe

And when this we rightly know

Thro the World we safely go

Joy & Woe are woven fine

A Clothing for the soul divine

Under every grief & pine

Runs a joy with silken twine

The Babe is more than swadling Bands

Throughout all these Human Lands

Tools were made & Born were hands

Every Farmer Understands

This week’s good things. The exhibition which I am currently in, with the Wild Pigment Project in Santa Fe’s Form and Concept Gallery, NM USA, has been extended until the New Year. You can see this extraordinary show curated by Tilke Elkins either in person at the gallery or online, where there is an excellent guide, here.

Tilke’s one woman show Records of Being Held, is also extended and it includes stunning large double-sided natural pigment paintings, designed to eventually be returned to earth. Her Reciprocal Foraging Guidelines are a continual source of inspiration and wisdom for me and countless other artists. I recommend immersing yourselves in her good words.

The time that has always existed since it was born a wild twin to our opposable thumbs, and is one of the few secret worm-holes back to the blessings of being a beast.

From what I have so far read about Benjamin’s jetztzeit, it is characterised very much like the Taoist Classics description of the ideal disposition of the body and spirit: timeless, poised, full of potential, filled with energy.

Benjamin’s jetztzeit: ‘a notion of time that is ripe with revolutionary possibility, time that has been detached from the continuum of history. It is time at a standstill, poised, filled with energy, and ready to take what Benjamin called the ‘tiger's leap’ into the future.’

It rang several bells for me from the Taoist Classics, which use traditional Chinese symbols of energy such as leaping tigers and diving birds of prey. Here’s one from the T’ai Chi Classics, which were to hand: ‘The form is like that of a falcon about to catch a rabbit.’

I apologise to David Stevenson as I say his first name wrongly in the audio version as ‘Davis’ from a typo on a comments thread, and noticed it too late to rectify it.

That reference to 'being a beast'... Charles Foster wrote an acclaimed book with that as the title. Have you read it and if so do you recommend it?

Thank you for this! I wholeheartedly agree, this culture has no idea what it has thrown away.