Stand your ground using softness

on 'being right' not being the point

This week I have been at home, though if I am honest, part of me is still in Somerset beside St Aldhelm’s spring. 1

I have also accepted that my writing here will be more personal than I had at first intended, so I have adjusted some of the wording and introductions on the landing page and About page, I have removed most instances of the word ‘Tao’, too, as it consistently delivers me angry men who wish to tell me (in interestingly spelled comments) just how selfish and awful a Daoist I am. Well, perhaps I am. So, I shall say I am a wayfarer2, in plain English. There is a path I can sense, and that I must follow, there’s no choice about this, for me.3 So, there it is, a nameless thing, and as such, not something for anyone else to get cross about. Of course, they still will, but by making no claims upon anyone else’s path, I can speak more freely. Also, line 2 of the Tao Te Ching in my favourite translation is, ‘Names can be assigned, but not permanent labels.’4 So, this is timely.

To swiftly sum up what’s in my updated welcome post, the Taoist Classics, 25 years of T’ai Chi Ch’uan, Stoic, Zen, Christian and other philosophy, Iain McGilchrist’s books and a great many novels and poems have helped me make sense of this journey. Then, with great joy, earth arts, natural materials, pigments and methods entered my life again in my 40s and the physicality of earth reiterated all the lessons I had learned in the empty hand years. Words are how I put them in order for myself, here. If anyone else is interested, great. If not, great. I don’t have a choice in the writing it down either, it seems. The Muse is singularly strict. He says, ‘write’, and until he says, ‘stop writing’, I shall continue.

The challenges

A series of interesting challenges has presented itself, one will be very public, others are private, and one regards health. All of them present the same conundrum at heart: how do I stand my ground using softness?

This seemingly oxymoronic term is used regularly by my T’ai Chi Master Mark Raudva as an elegant way of describing what an ideal yield in pushing hands is like: we neither lean nor incline, we do not resist, we turn around our upright central axis, we allow the push to turn us. On encountering this, a pusher who keeps doggedly pushing falls into emptiness, often loses their balance and must step or fall over, like Wile-e-coyote at the cliff’s edge. Whereas the person who connects, pays attention and yields, allows themself to be turned, is able to remain standing where they are without the use of force.

The traditional instruction is to be like water5, neither to shrink away, nor block. We are not being doormats; the yin quality of yielding is full of receptive energy, it is not achieved by negating ourselves. Imagine punching a bath full of water, it gives way under your fist… and returns to splash you in the face with precisely the same amount of force as you gave it. Or we could mention the ‘mill-wheel principle’, where pushing one side away means the other side simultaneously advances as it turns around its axle. Mill-wheels may now be uncommon, but a revolving door is the ideal contemporary image.

For a chronically defended, fearful, avoidant fourteen year old, stepping into a room full of people practising soft, vigorous pushing hands was the greatest challenge. What was going on? Were they fighting? But they were smiling! It seemed serious, yet light-hearted. On and on the dichotomous pairs stacked up in my mind, as I watched these adults playing, or doing spiritual practice, or martial arts, or whatever the hell it was they were doing. Today I remember the mental tower of embodied koans, and with a neat ‘kkkrraakk’ my stirring mind’s defence gave out, and my spirit leapt through the crack and thereby saved my life.6

Diagrams

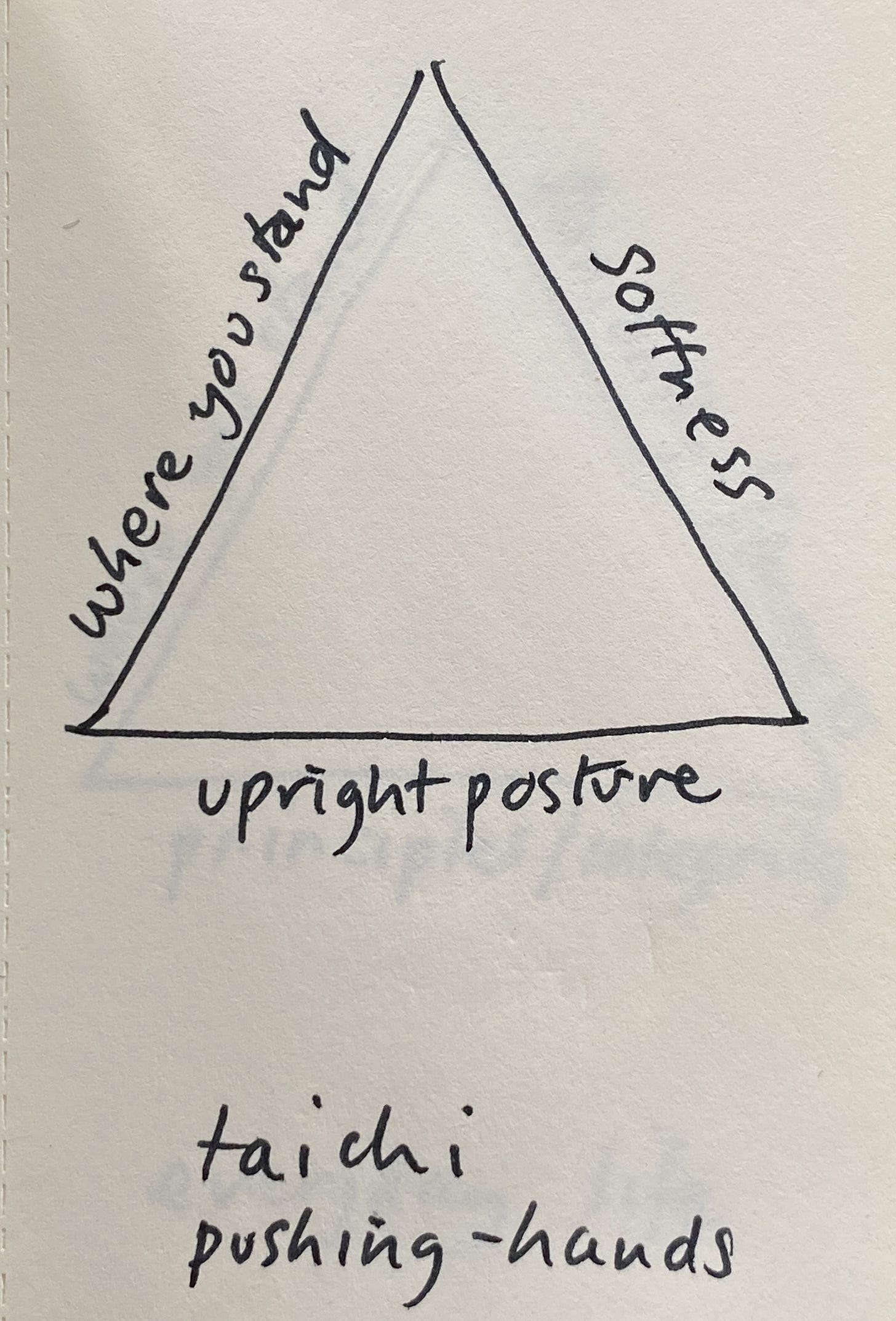

In the diagram above, the triangle shows three qualities present when pushing hands in the style of my Great Grandmaster, Dr Chi Chiang-Tao7: one’s upright posture (our style does not lean, unlike some others), softness (as opposed to blocking or the use of force), and finally, the place where one is standing. Each style of T’ai Chi varies slightly, or greatly, one from another. Think of it as like Jazz, or Football, or The Left, and you’ll get an idea about how many opinions about these things there are out there. In our particular style, the use of resistant force is always considered a mistake, as non-resistance is prioritised over ‘winning’, or standing right where we are and not being moved. In all my years teaching T’ai Chi I am not sure I ever filmed this, as students were constantly practising it, many hundreds of times per session, back and forth! But I have found a few photos.

In the triangle above you can have only two sides at once (like the cost / speed / quality8 one I mentioned a few weeks ago). If I wish to remain on my little piece of ground, and not lose my uprightness, I must give up my softness, as I will need to resist the other person’s push to succeed. This is about being right, and winning at all costs. There is always a price to pay, and it is usually the quality of the relationship.

If I want to stay soft and upright, I must allow the push to move me from my little spot, (not a big deal in my style, unless on a cliff edge, say…) But always giving up your ground can be demoralising, and lead to a retreating mind, literally, ‘being on the back foot’. Plus, a bully will relish this, and be emboldened.

If I prioritise standing my ground and my softness, then I will surely lose my posture and start bending wildly and writhing, what we call doing ‘tofu T’ai Chi’ or just simply ‘noodling’. I’ll lose my integrity.

Why does this matter to anyone not interested in T’ai Chi?

Well, it’s how I learned to stop fighting life. It took ten years to get reasonably good at pushing hands. But each year, I noticed interpersonal relationships were less fraught, stuck places moved more easily, things that used to upset me seemed to have no place to land. Only the really big things were getting me off balance, both in class and in life. I started to actively seek out the guys in my teacher’s school who used to push me around easily and whom I’d always avoided. Each month, their pushes and grabs were easier to deal with, and I could easily feel them coming. This is testament to how well my teacher taught us, and to the power of sustained practice to transform habitual tendencies.

In the triangle above, you can still only have two sides in their ideal way at once. When life challenges me and I decide to hold to my principles (ie. remain upright), and stay sensitive, connected and soft, rather than angry, disconnected and desensitized, then I may have to leave a situation that has become unhealthy, this doesn’t imply blame of either party. I just have to change where I am standing. Some people call this ‘having boundaries’, but it comes in all kinds of forms. It can be sad, having to leave, but it is better than selling out.

Other times, when life pushed me, I have sometimes gone against my own integrity or principles, to stay where I am (or continue to have what I want) and to maintain the appearance of being soft and connected. As you can imagine, this feels awful inside, is basically a lie, and leads to a shrivelling of the soul. Plus, it always came back to bite me. So I had give that one up, as nothing I grasped was worth the soul-cost.

A good yield

Lastly, is standing one’s ground using softness. This means standing firm and rooted in a place I know to be good and true, a standpoint, rather than an opinion, say. But also adhering to my principles. This will require me to be incredibly soft, to really yield, to not try to control the situation or bring another person round to exactly my way of seeing things. Put simply, I will have to allow the push, and not resist it, argue it down or refute it. I may even have to let it change me. This is what happens when someone dear to us, with whom we disagree, but with whom we must yet stay in connexion, offers us in good faith their contrasting view / push / standpoint / way of life. This is almost always so with at least someone in our own family, and sometimes happens with partners or good friends. If they did not mean so much to us, we could just step away (option 1). Or if we didn’t care about life, we could just noodle, lie, wriggle or engage in machinations… (option 2).

So I find myself, for the hundredth time, about to consider option three, which is of course not an option but an obligation. Because it takes into account the whole of the context - the wider relationship, society, the Earth, ongoing reciprocity and the possibility of remaining in communion with someone, of learning something. It will often feel uncomfortable, challenging, and difficult, but I discovered over the years that it has a consistent outcome, whether in T’ai Chi push hands or in everyday life.

It’s this: once it is over, there is no residual feeling of unresolvedness or ‘stickiness’, because we haven’t compromised our integrity. And the same push never unsettles us again, because we have really yielded, and the memory stays in the body and in the heart as real knowledge. 9

So, wish me luck as I settle my desire to be proved right, drop my addiction to ‘positive’ outcomes, and soften my aversion to difficult ongoing situations. I intend to practice listening, softness, firmness where necessary, and allow sadness and change if they arise. To ‘stay with the trouble’, rather than run away or refuse to engage, in this instance, (which is of course occasionally a sometimes necessary move in life). I can give no guarantee that I will succeed or that it will even go well. If there is anything I can report back, I shall. Apologies for being gnomic. But then, perhaps it will leave space for your own experiences to overlay my words. Feel free to share your own stories below.

When we can regularly respond to life’s pushes freely, without our habitual fears hampering our response-ability, we can say that we have truly yielded to our own conditioning, (a wonderful phrase from my late Grandmaster, John Kells). A fight is suddenly transformed into a fascinating interplay of energy. An ideological conflict is seen for what it often is - the juxtaposition of people in good faith wanting to make a positive contribution to the world. The possibility for mutual respect, love and friendship vastly increases, and even if we must finally go our own separate ways, we are more likely to do so in peace and without recrimination.

This week’s good thing: By the time you read this I will have returned from the launch of

‘s new book Here Be Monsters in London’s Hoxton Bookstore. I love Rhyd’s Substack and his clear, warm writing helps me understand diverse things I have studiously avoided, such as Marxist theory, the culture wars and correct gym etiquette. So, it was great to meet Rhyd and his husband in person on Friday and introduce them to some of my friends after his talk. I am a couple of chapters in and it’s great. More on this book when I have finished reading it.I have a cold and a blocked up nose this week, excuse the less than excellent voiceover quality.

Tao = ‘Way’.

Which is something I once heard one of my Grandmaster’s indoor students say in 2006, and did not understand at the time. Now I say the exact same thing.

by Thomas Cleary, Shambala Editions.

‘Water is the highest good’ Tao Te Ching and T’ai Chi Classics

Thankyou Richard Siwiak for 3 years of superb classes, which introduced me to practice of the Way.

The supreme yielder of his generation, also, interestingly, both a Taoist and a Christian.

Cost, speed, quality - I say this wrongly in the voiceover, apologies.

Alchemically, ‘True Lead’.

I don’t have anything profound to say - just that I appreciate your posts so much, they always introduce me to new and inspiring ways of looking at things - thank you!

Hello Caro.

Hope your cold is departing.

Bizarre - and literally ridiculous - for anyone to call anyone else an “awful Daoist” !

I feel the same about the muse!

My tai chi teacher Keith Good often uses the revolving door metaphor in relation to push hands and frame development.